Question: what was the landscape like in Merovingian northern Gaul?

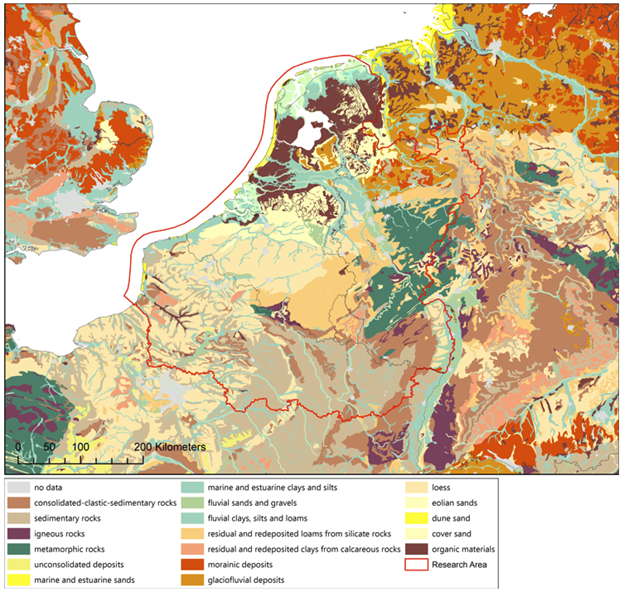

To have an idea of what the landscape was like in the early medieval period, I made the map below a while ago. It shows the main soil and paleo-geographical features of northwestern Europe in the Early Middle Ages. The supposition here being that most of the geology and geomorphology of northwestern Europe have not changed dramatically since the Early Middle Ages. At least, not on a scale that would be visible on a small-scale map like this. The major exception to this rule being, of course, the Netherlands. Fortunately the Atlas of the Holocene is available (downloadable from the Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency) and can be plotted on top of the geological information of the rest of Europe as can be retrieved from the European Soil Database (downloadable from Eurostat).

Although this map looks very accurate and complete, a better map can be imagined to help with your archaeological interpretations. Yes, it does show what the soil consists of, but no, it is not a nice map to use as a background to plot your archaeological distributions on; the dots would simply get lost in all the different colors.

The solution would then be to simplify the map-legend. But to simplify the legend into something even more meaningful than just putting everything on display, is to ask a different question: What is it exactly in the landscape that matters? If the answer to that question is ‘geology’, then this is indeed the map for you. But it probably is not geology by itself, but geology as a proxy for ecology.

Knowledge of the geology and ecology in which local communities carved out a living is fundamental to the understanding of their day-to-day activities and social organization. But let me make two points about this very clear before we take this discussion any further. First, the landscape does not determine the way people make their living. Yes, the environment (vis-à-vis the available knowledge and technology) poses outer limits on what can be done in a locality, because of e.g. the amount of rain, average summer temperature, length of the growing season, daily or seasonal flooding, etc. But within these limits social aspects are often more decisive in the choice for livelihood strategies than environmental factors are. Second, at the other end of the spectrum, a precise ethnographic ecology is not attainable to us right now. I would assume that local communities had a knowledge of the ecology and geology far more precise than is visible in the above map. Or in any map we have, since probably a different science was used to classify things, according to different meanings and values.

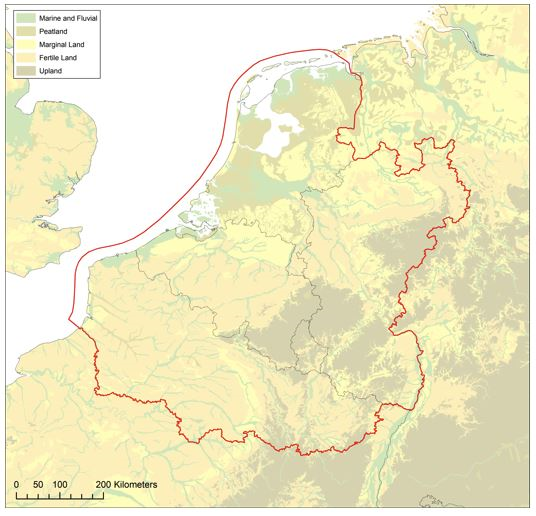

The above map is thus too precise and not precise enough at the same time. The challenge then is to simplify the landscape in a way that it can function as a frame to interpret the archaeology of early medieval Europe. A simplified landscape is therefore presented in the map below. The main ecological settings are determined on the localities’ relationship with surface water (marine, fluvial and peat), natural agricultural productivity of the soil (not natural climax vegetation) and altitude.

These ecological settings will undoubtedly have had various meanings for local communities, but they most importantly serve as major agronomic conditions for growing crops regardless of the local cultural system. Again, nothing is completely determined by these ecological settings: with determination and technology any landscape can be brought under the plough successfully. So, this map does not serve as a frame to determine who was doing what and where, but it provides an indication of the amount of determination and ingenuity it takes to pursue certain livelihood strategies in certain localities.